Sunday, September 18, 2011 (continued)

After the required check of our ID’s, and a sweep of the undercarriage of the truck for explosives, we were granted access to the compound. As we cleared a second security gate, I observed a training exercise involving two men lying face down on the ground, amidst a number of on-lookers. The only the men in uniform were those dealing with the prone individuals. I had expected everyone on base to be wearing the ANCOP (Afghanistan National Civil Order Police) uniform, but most wore the traditional Afghan garb (or as we referred to them, man-jams). I was told that since the compound was also an assembly point for police officers awaiting a permanent assignment, or coming back from leave, many were authorized to be in their civilian clothes. Still, others had not yet received their official ANCOP uniforms.

After the required check of our ID’s, and a sweep of the undercarriage of the truck for explosives, we were granted access to the compound. As we cleared a second security gate, I observed a training exercise involving two men lying face down on the ground, amidst a number of on-lookers. The only the men in uniform were those dealing with the prone individuals. I had expected everyone on base to be wearing the ANCOP (Afghanistan National Civil Order Police) uniform, but most wore the traditional Afghan garb (or as we referred to them, man-jams). I was told that since the compound was also an assembly point for police officers awaiting a permanent assignment, or coming back from leave, many were authorized to be in their civilian clothes. Still, others had not yet received their official ANCOP uniforms.

|

| Afghan men in their local dress, as they appeared on the training compound |

Up to this

point the only people in this style of dress with whom I had interacted, were

the local workers on Camp Pinnacle.

But even there, they were always outnumbered by the other workers who

wore western styles and by us in “contractor” clothing. Dressed as I was, I was now in

the minority. This helped me

realize how prejudiced I had become by associating a certain style of dress

with “the bad guys”. So now, here

I was among all these “possible terrorists”. I began thinking more rationally, “Certainly, they can’t all

be members of the Taliban, al-Qaeda, or the insurgency.” Well, I hoped, anyway!

|

| The compound's front/main building below an empty billboard. The two men in the foreground are language assistants. |

The site itself had been some type of manufacturing plant during the

Russian occupation. There was a

large building that housed administrative offices and lodging for select ANCOP

members. The others were quartered

in tents, behind the building and throughout the compound. The building’s roof provided “high

ground” upon which small guard towers were positioned along strategic

points. The shell of another

building was situated to the rear of the main building, and at a lower

elevation. Within its walls stood

tents where the less fortunate were housed. They were, however, heated and cooled.

|

| Tents in which many of the officers were housed |

|

| Interior view of the spartan conditions in the tents |

|

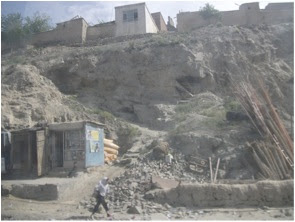

| One of the rear buildings still bearing the remnants of previous years' fighting |

As we

dismounted from our trucks, I followed my coworkers’ lead in removing our body

armor. While, physically, it was a

relief to have the extra weight lifted off our shoulders, the prospect of

wearing less protection was somewhat troubling. Probably sensing my unease, Kenny, one of our team leads

instructed, “It’s relatively safe here.

But we always try to stay in pairs when we move around the

compound,” - his advice seemed to

conflict with his security assessment of the facility. As our small contingent of contractors

walked among the man jams, I noted how at ease my colleagues seemed. I, on the other hand, despite my best

effort to look nonchalant, felt as though I had the “deer in the headlights

look”. Some of my anxiety was due

to my perception (whether true or not), that I seemed to be attracting more

stares and attention than were my comrades. Again, I chalked that up to being the “new kid on the

block”.

I was introduced

to a few of the LA’s (language assistants). All were quite friendly and seemed eager to be of

service. Only one wore the

manjams; the others were dressed in western-type clothing. A few wore a mixture of clothing types

and styles. With these, one could

discern with some accuracy, some of their previous working partners. For example, one LA wore military

issued combat boots, contractor pants, and a NY Jets jersey. In discussing whom he had worked for in

the past, he indicated that he had worked with a US Marine unit, and a

contractor who liked the Jets – therefore, the reason for his “multiple

personality” dress.

|

| Me and Brooks Sanderson (in baseball caps) and 4 of the LAs |

For my first

day I would be shadowing Bill, a retired Maryland trooper. As he drilled weapons manipulation and

reloading exercises for the AK-47, I was impressed by his professional demeanor

and how he presented himself to the Afghan students. I was surprised by how much of a delay was caused by the

translation from English to Dari, the primary language spoken in Kabul. It

seemed to take away from the flow of the lesson. I wondered how it would affect my own teaching style. Hell, I lose my train of thought while

I’m speaking English; let alone having to wait for someone to translate!

I was

introduced to Hashimi, a young LA who would be my primary interpreter. He was 22, lean, athletic, stood about

6’, and was an avid boxer. He had

a good nature about him, and it wasn’t long before he could easily understand

my jokes. Nor did it take me

long to learn that humor doesn’t always translate well – that’s where Hashimi

was worth his weight in gold.

The first

time I took a stab at being humorous, I recall Hashimi pausing and shooting me

a serious look. The stare was

followed by silence. As if he were

attempting to hide his non-verbal communication to me, he shook his head ever

so slightly from side to side, as if to say, “Don’t go there!” When the lesson was over he simply

said, “That would have not been good.”

He then explained some of the cultural nuances, and that to have

translated the joke, would have probably crossed the line. I took his word for it. Being thankful that he prevented me

from becoming embroiled in some kind of international incident, I expressed my

gratitude for using his better judgment and asked him to feel free to censor me

in the future.

It wasn’t

that Hashimi disapproved. He was very open-minded, to the point of

regularly requesting jokes of me.

He was just being protective of my (and probably his) welfare. Such is the importance of a good

relationship with an interpreter.

|

| Hashimi, my language assistant... |

|

| ....flashing the obligatory gang sign. |

At the

conclusion of training, as Bill, Hashimi, and I made our way through the crowd

of manjams, I asked Hashimi why so many people seemed to be staring at me. He told me that they thought I was an

Afghan, but they couldn’t figure out why I was dressed the way I was.

Once back in

the truck I was informed that the “training” we witnessed as we pulled into the

compound earlier that morning wasn’t training at all. Instead, the men that were being searched on the ground were

two suspected insurgents attempting to gain entry into the compound.

It’s going to be an interesting place to

work.